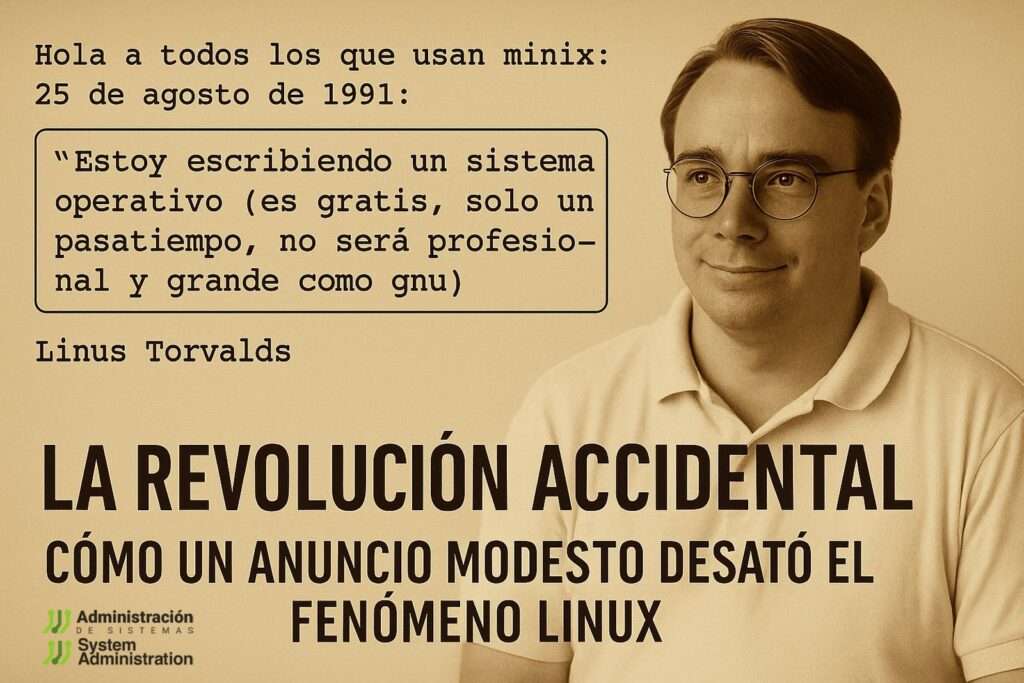

Linus Torvalds anunció su nuevo sistema operativo como un simple hobby sin pretensiones. Tres décadas después, es la columna vertebral del mundo digital.

El 25 de agosto de 1991, un joven estudiante de informática en la Universidad de Helsinki llamado Linus Benedict Torvalds escribió un mensaje en el grupo de noticias comp.os.minix. Nadie en aquel foro —poblado por entusiastas de los sistemas operativos tipo Unix— imaginaba que aquella publicación marcaría un antes y un después en la historia del software. Con tono casual y sin grandilocuencia, Torvalds describía su proyecto como “un sistema operativo (gratis) (solo un hobby, no será grande y profesional como GNU)”. Aquella frase, hoy célebre, constituye posiblemente una de las predicciones más erróneas de la historia de la informática moderna.

Un proyecto de aprendizaje que se convirtió en revolución

En realidad, el germen de Linux había comenzado unos meses antes. En abril de 1991, Torvalds empezó a trabajar en un pequeño núcleo (kernel) para ordenadores compatibles con los procesadores Intel 386 y 486. Como él mismo relató más tarde, no partía con la intención de escribir un sistema operativo completo, sino de aprender cómo funcionaban las rutinas de conmutación de tareas del 386 y profundizar en la arquitectura de bajo nivel.

Los primeros experimentos eran tan rudimentarios que para depurar el código Linus utilizaba bucles de muerte (“jmp die”) en ensamblador. El simple hecho de provocar un cuelgue sin reiniciar el sistema era un logro. Aquel entorno, sin herramientas gráficas, sin depuradores funcionales en modo protegido y sin apenas documentación fiable, suponía un reto formidable.

La chispa que encendió la mecha: el mensaje del 25 de agosto

El mensaje original de Linus incluía una pequeña encuesta a la comunidad Minix (un sistema educativo creado por Andrew Tanenbaum) sobre qué características les gustaría ver en un sistema similar. “Estoy haciendo un sistema operativo gratuito para clones AT de 386(486)”, escribió. “Esto se ha estado cocinando desde abril y está empezando a estar listo”. En aquel momento, el sistema apenas podía ejecutar bash y gcc, y estaba lleno de limitaciones: no era portátil, no tenía soporte para disquetes ni para discos SCSI, y su biblioteca estándar era muy básica.

Aun así, la comunidad respondió con interés. Algunos incluso pidieron ser beta testers. Apenas dos semanas después, Torvalds subió a un servidor FTP finlandés (nic.funet.fi) los primeros archivos fuente de lo que llamó Linux 0.01. No era funcional: no incluía binarios y requería un sistema Minix para compilarse. Fue una versión simbólica, un gesto para demostrar que su trabajo avanzaba.

De la oscuridad al primer uso práctico

El 5 de octubre de 1991, Linus publicó la versión 0.02. Esta ya incluía algunos binarios básicos —como bash, update y gcc— y podía ejecutar algunas tareas Unix sencillas. Aunque la instalación seguía siendo compleja y dependiente de Minix, Linux empezaba a atraer a otros programadores. Versiones posteriores como 0.03 y 0.10 mejoraron sustancialmente la estabilidad y funcionalidades.

La 0.11, lanzada en diciembre de 1991, marcó el inicio del desarrollo autónomo: Linux ya podía autocompilarse y se independizaba de Minix. Incluía controladores de disquete, un sistema de archivos más estable, y hasta el sonido de “beep” en la consola. El kernel comenzaba a ser usable por un público más amplio.

La sinergia con GNU y el salto a la madurez

Lo que permitió a Linux despegar definitivamente fue su integración con las herramientas del proyecto GNU, iniciado por Richard Stallman en 1983. GNU había desarrollado compiladores, bibliotecas, y herramientas de línea de comandos, pero seguía sin tener un núcleo funcional: el Hurd, aún en desarrollo, no lograba despegar. Linux llenó ese vacío.

Gracias a su compatibilidad con las herramientas GNU, las primeras distribuciones funcionales de GNU/Linux —como MCC Interim, Slackware y Debian— comenzaron a aparecer entre 1992 y 1993. La comunidad creció exponencialmente. En enero de 1992 se publicó Linux 0.12, bajo la licencia GPL, lo que facilitó su adopción y colaboración masiva.

Una ironía histórica: “No será grande y profesional como GNU”

Treinta años más tarde, esa frase inicial de Torvalds resulta casi cómica. Linux no solo se convirtió en un sistema operativo “grande y profesional”, sino que se ha consolidado como pilar de la infraestructura digital global:

- Más del 95 % de los servidores más potentes del mundo utilizan Linux.

- Android, el sistema operativo móvil más usado del planeta, tiene un núcleo Linux.

- Está presente en supercomputadoras, centros de datos, routers, coches, satélites y televisores.

- Es la plataforma dominante en entornos cloud, inteligencia artificial, contenedores (como Docker) y sistemas embebidos.

Además, aunque muchas distribuciones utilizan componentes GNU, no todas lo hacen. Ejemplos como Android, Alpine Linux o sistemas con BusyBox muestran cómo Linux ha trascendido incluso al ecosistema para el que fue pensado originalmente.

Conclusión: de hobby personal a fenómeno global

Lo que Linus Torvalds inició como un proyecto para aprender sobre los entresijos del procesador 386 terminó por cambiar la historia de la informática. Su historia demuestra cómo una combinación de curiosidad técnica, colaboración abierta y distribución libre puede originar una revolución tecnológica sin precedentes.

Aquel mensaje de agosto de 1991 ya forma parte del folclore de Internet. Y su autor, lejos de equivocarse por falta de visión, acertó en lo más importante: el software libre era el camino. Solo subestimó lo lejos que podía llegar su “hobby”.

Mensaje original en inglés

LINUX’s History

Note: The following text was written by Linus on July 31 1992. It is a collection of various artifacts from the period in which Linux first began to take shape. This is just a sentimental journey into some of the first posts concerning linux, so you can happily press 'n' now if you actually thought you'd get anything technical. From: [email protected] (Linus Benedict Torvalds) Newsgroups: comp.os.minix Subject: Gcc-1.40 and a posix-question Message-ID: Date: 3 Jul 91 10:00:50 GMT Hello netlanders, Due to a project I'm working on (in minix), I'm interested in the posix standard definition. Could somebody please point me to a (preferably) machine-readable format of the latest posix rules? Ftp-sites would be nice. The project was obviously linux, so by July 3rd I had started to think about actual user-level things: some of the device drivers were ready, and the harddisk actually worked. Not too much else. As an aside for all using gcc on minix - [ deleted ] Just a success-report on porting gcc-1.40 to minix using the 1.37 version made by Alan W Black & co. Linus Torvalds [email protected] PS. Could someone please try to finger me from overseas, as I've installed a "changing .plan" (made by your's truly), and I'm not certain it works from outside? It should report a new .plan every time. So I was clueless - had just learned about named pipes. Sue me. This part of the post got a lot more response than the actual POSIX query, but the query did lure out arl from the woodwork, and we mailed around for a bit, resulting in the Linux subdirectory on nic.funet.fi. Then, almost two months later, I actually had something working: I made sources for version 0.01 available on nic sometimes around this time. 0.01 sources weren't actually runnable: they were just a token gesture to arl who had probably started to despair about ever getting anything. This next post must have been from just a couple of weeks before that release. From: [email protected] (Linus Benedict Torvalds) Newsgroups: comp.os.minix Subject: What would you like to see most in minix? Summary: small poll for my new operating system Message-ID: Date: 25 Aug 91 20:57:08 GMT Organization: University of Helsinki Hello everybody out there using minix - I'm doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won't be big and professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones. This has been brewing since april, and is starting to get ready. I'd like any feedback on things people like/dislike in minix, as my OS resembles it somewhat (same physical layout of the file-system (due to practical reasons) among other things). I've currently ported bash(1.08) and gcc(1.40), and things seem to work. This implies that I'll get something practical within a few months, and I'd like to know what features most people would want. Any suggestions are welcome, but I won't promise I'll implement them :-) Linus ([email protected]) PS. Yes - it's free of any minix code, and it has a multi-threaded fs. It is NOT protable (uses 386 task switching etc), and it probably never will support anything other than AT-harddisks, as that's all I have :-(. Judging from the post, 0.01 wasn't actually out yet, but it's close. I'd guess the first version went out in the middle of September -91. I got some responses to this (most by mail, which I haven't saved), and I even got a few mails asking to be beta-testers for linux. After that just a few general answers to quesions on the net: From: [email protected] (Linus Benedict Torvalds) Newsgroups: comp.os.minix Subject: Re: What would you like to see most in minix? Summary: yes - it's nonportable Message-ID: Date: 26 Aug 91 11:06:02 GMT Organization: University of Helsinki In article [email protected] (Jyrki Kuoppala) writes: >> [re: my post about my new OS] > >Tell us more! Does it need a MMU? Yes, it needs a MMU (sorry everybody), and it specifically needs a 386/486 MMU (see later). > >>PS. Yes - it's free of any minix code, and it has a multi-threaded fs. >>It is NOT protable (uses 386 task switching etc) > >How much of it is in C? What difficulties will there be in porting? >Nobody will believe you about non-portability ;-), and I for one would >like to port it to my Amiga (Mach needs a MMU and Minix is not free). Simply, I'd say that porting is impossible. It's mostly in C, but most people wouldn't call what I write C. It uses every conceivable feature of the 386 I could find, as it was also a project to teach me about the 386. As already mentioned, it uses a MMU, for both paging (not to disk yet) and segmentation. It's the segmentation that makes it REALLY 386 dependent (every task has a 64Mb segment for code & data - max 64 tasks in 4Gb. Anybody who needs more than 64Mb/task - tough cookies). It also uses every feature of gcc I could find, specifically the __asm__ directive, so that I wouldn't need so much assembly language objects. Some of my "C"-files (specifically mm.c) are almost as much assembler as C. It would be "interesting" even to port it to another compiler (though why anybody would want to use anything other than gcc is a mystery). Note: linux has in fact gotten more portable with newer versions: there was a lot more assembly in the early versions. It has in fact been ported to other architectures by now. Unlike minix, I also happen to LIKE interrupts, so interrupts are handled without trying to hide the reason behind them (I especially like my hard-disk-driver. Anybody else make interrupts drive a state- machine?). All in all it's a porters nightmare. >As for the features; well, pseudo ttys, BSD sockets, user-mode >filesystems (so I can say cat /dev/tcp/kruuna.helsinki.fi/finger), >window size in the tty structure, system calls capable of supporting >POSIX.1. Oh, and bsd-style long file names. Most of these seem possible (the tty structure already has stubs for window size), except maybe for the user-mode filesystems. As to POSIX, I'd be delighted to have it, but posix wants money for their papers, so that's not currently an option. In any case these are things that won't be supported for some time yet (first I'll make it a simple minix- lookalike, keyword SIMPLE). Linus ([email protected]) PS. To make things really clear - yes I can run gcc on it, and bash, and most of the gnu [bin/file]utilities, but it's not very debugged, and the library is really minimal. It doesn't even support floppy-disks yet. It won't be ready for distribution for a couple of months. Even then it probably won't be able to do much more than minix, and much less in some respects. It will be free though (probably under gnu-license or similar). Well, obviously something worked on my machine: I doubt I had yet gotten gcc to compile itself under linux (or I would have been too proud of it not to mention it). Still before any release-date. Then, October 5th, I seem to have released 0.02. As I already mentioned, 0.01 didn't actually come with any binaries: it was just source code for people interested in what linux looked like. Note the lack of announcement for 0.01: I wasn't too proud of it, so I think I only sent a note to everybody who had shown interest. From: [email protected] (Linus Benedict Torvalds) Newsgroups: comp.os.minix Subject: Free minix-like kernel sources for 386-AT Message-ID: Date: 5 Oct 91 05:41:06 GMT Organization: University of Helsinki Do you pine for the nice days of minix-1.1, when men were men and wrote their own device drivers? Are you without a nice project and just dying to cut your teeth on a OS you can try to modify for your needs? Are you finding it frustrating when everything works on minix? No more all- nighters to get a nifty program working? Then this post might be just for you :-) As I mentioned a month(?) ago, I'm working on a free version of a minix-lookalike for AT-386 computers. It has finally reached the stage where it's even usable (though may not be depending on what you want), and I am willing to put out the sources for wider distribution. It is just version 0.02 (+1 (very small) patch already), but I've successfully run bash/gcc/gnu-make/gnu-sed/compress etc under it. Sources for this pet project of mine can be found at nic.funet.fi (128.214.6.100) in the directory /pub/OS/Linux. The directory also contains some README-file and a couple of binaries to work under linux (bash, update and gcc, what more can you ask for :-). Full kernel source is provided, as no minix code has been used. Library sources are only partially free, so that cannot be distributed currently. The system is able to compile "as-is" and has been known to work. Heh. Sources to the binaries (bash and gcc) can be found at the same place in /pub/gnu. ALERT! WARNING! NOTE! These sources still need minix-386 to be compiled (and gcc-1.40, possibly 1.37.1, haven't tested), and you need minix to set it up if you want to run it, so it is not yet a standalone system for those of you without minix. I'm working on it. You also need to be something of a hacker to set it up (?), so for those hoping for an alternative to minix-386, please ignore me. It is currently meant for hackers interested in operating systems and 386's with access to minix. The system needs an AT-compatible harddisk (IDE is fine) and EGA/VGA. If you are still interested, please ftp the README/RELNOTES, and/or mail me for additional info. I can (well, almost) hear you asking yourselves "why?". Hurd will be out in a year (or two, or next month, who knows), and I've already got minix. This is a program for hackers by a hacker. I've enjouyed doing it, and somebody might enjoy looking at it and even modifying it for their own needs. It is still small enough to understand, use and modify, and I'm looking forward to any comments you might have. I'm also interested in hearing from anybody who has written any of the utilities/library functions for minix. If your efforts are freely distributable (under copyright or even public domain), I'd like to hear from you, so I can add them to the system. I'm using Earl Chews estdio right now (thanks for a nice and working system Earl), and similar works will be very wellcome. Your (C)'s will of course be left intact. Drop me a line if you are willing to let me use your code. Linus PS. to PHIL NELSON! I'm unable to get through to you, and keep getting "forward error - strawberry unknown domain" or something. Well, it doesn't sound like much of a system, does it? It did work, and some people even tried it out. There were several bad bugs (and there was no floppy-driver, no VM, no nothing), and 0.02 wasn't really very useable. 0.03 got released shortly thereafter (max 2-3 weeks was the time between releases even back then), and 0.03 was pretty useable. The next version was numbered 0.10, as things actually started to work pretty well. The next post gives some idea of what had happened in two months more... From: [email protected] (Linus Benedict Torvalds) Newsgroups: comp.os.minix Subject: Re: Status of LINUX? Summary: Still in beta Message-ID: Date: 19 Dec 91 23:35:45 GMT Organization: University of Helsinki In article [email protected] (Miquel van Smoorenburg) writes: >Hello *, > I know some people are working on a FREE O/S for the 386/486, >under the name Linux. I checked nic.funet.fi now and then, to see what was >happening. However, for the time being I am without FTP access so I don't >know what is going on at the moment. Could someone please inform me about it ? >It's maybe best to follow up to this article, as I think that there are >a lot of potential interested people reading this group. Note, that I don't >really *have* a >= 386, but I'm sure in time I will. Linux is still in beta (although available for brave souls by ftp), and has reached the version 0.11. It's still not as comprehensive as 386-minix, but better in some respects. The "Linux info-sheet" should be posted here some day by the person that keeps that up to date. In the meantime, I'll give some small pointers. First the bad news: - Still no SCSI: people are working on that, but no date yet. Thus you need a AT-interface disk (I have one report that it works on an EISA 486 with a SCSI disk that emulates the AT-interface, but that's more of a fluke than anything else: ISA+AT-disk is currently the hardware setup) As you can see, 0.11 had already a small following. It wasn't much, but it did work. - still no init/login: you get into bash as root upon bootup. That was still standard in the next release. - although I have a somewhat working VM (paging to disk), it's not ready yet. Thus linux needs at least 4M to be able to run the GNU binaries (especially gcc). It boots up in 2M, but you cannot compile. I actually released a 0.11+VM version just before Christmas -91: I didn't need it myself, but people were trying to compile the kernel in 2MB and failing, so I had to implement it. The 0.11+VM version was available only to a small number of people that wanted to test it out: I'm still surprised it worked as well as it did. - minix still has a lot more users: better support. - it hasn't got years of testing by thousands of people, so there are probably quite a few bugs yet. Then for the good things.. - It's free (copyright by me, but freely distributable under a very lenient copyright) The early copyright was in fact much more restrictive than the GNU copyleft: I didn't allow any money at all to change hands due to linux. That changed with 0.12. - it's fun to hack on. - /real/ multithreading filesystem. - uses the 386-features. Thus locked into the 386/486 family, but it makes things clearer when you don't have to cater to other chips. - a lot more... read my .plan. /I/ think it's better than minix, but I'm a bit prejudiced. It will never be the kind of professional OS that Hurd will be (in the next century or so :), but it's a nice learning tool (even more so than minix, IMHO), and it was/is fun working on it. Linus ([email protected]) ---- my .plan -------------------------- Free UNIX for the 386 - coming 4QR 91 or 1QR 92. The current version of linux is 0.11 - it has most things a unix kernel needs, and will probably be released as 1.0 as soon as it gets a little more testing, and we can get a init/login going. Currently you get dumped into a shell as root upon bootup. Linux can be gotten by anonymous ftp from 'nic.funet.fi' (128.214.6.100) in the directory '/pub/OS/Linux'. The same directory also contains some binary files to run under Linux. Currently gcc, bash, update, uemacs, tar, make and fileutils. Several people have gotten a running system, but it's still a hackers kernel. Linux still requires a AT-compatible disk to be useful: people are working on a SCSI-driver, but I don't know when it will be ready. There are now a couple of other sites containing linux, as people have had difficulties with connecting to nic. The sites are: Tupac-Amaru.Informatik.RWTH-Aachen.DE (137.226.112.31): directory /pub/msdos/replace tsx-11.mit.edu (18.172.1.2): directory /pub/linux There is also a mailing list set up '[email protected]'. To join, mail a request to '[email protected]'. It's no use mailing me: I have no actual contact with the mailing-list (other than being on it, naturally). Mail me for more info: Linus ([email protected]) 0.11 has these new things: - demand loading - code/data sharing between unrelated processes - much better floppy drivers (they actually work mostly) - bug-corrections - support for Hercules/MDA/CGA/EGA/VGA - the console also beeps (WoW! Wonder-kernel :-) - mkfs/fsck/fdisk - US/German/French/Finnish keyboards - settable line-speeds for com1/2 As you can see: 0.11 was actually stand-alone: I wrote the first mkfs/fsck/fdisk programs for it, so that you didn't need minix any more to set it up. Also, serial lines had been hard-coded to 2400bps, as that was all I had. Still lacking: - init/login - rename system call - named pipes - symbolic links Well, they are all there now: init/login didn't quite make it to 0.12, and rename() was implemented as a patch somewhere between 0.12 and 0.95. Symlinks were in 0.95, but named pipes didn't make it until 0.96. Note: The version number went directly from 0.12 to 0.95, as the follow-on to 0.12 was getting feature-full enough to deserve a number in the 0.90's 0.12 will probably be out in January (15th or so), and will have: - POSIX job control (by tytso) - VM (paging to disk) - Minor corrections Actually, 0.12 was out January 5th, and contained major corrections. It was in fact a very stable kernel: it worked on a lot of new hardware, and there was no need for patches for a long time. 0.12 was also the kernel that "made it": that's when linux started to spread a lot faster. Earlier kernel releases were very much only for hackers: 0.12 actually worked quite well. Note: The following document is a reply by Linus Torvalds, creator of Linux, in which he talks about his experiences in the early stages of Linux development To: [email protected] From: [email protected] (Linus Benedict Torvalds) Subject: Re: Writing an OS - questions !! Date: 5 May 92 07:58:17 GMT In article [email protected] (V. Narayanan) writes: Hi folks, For quite some time this "novice" has been wondering as to how one goe s about the task of writing an OS from "scratch". So here are some questions, and I would appreciate if you could take time to answer 'em. Well, I see someone else already answered, but I thought I'd take on the linux-specific parts. Just my personal experiences, and I don't know how normal those are. 1) How would you typically debug the kernel during the development phase? Depends on both the machine and how far you have gotten on the kernel: on more simple systems it's generally easier to set up. Here's what I had to do on a 386 in protected mode. The worst part is starting off: after you have even a minimal system you can use printf etc, but moving to protected mode on a 386 isn't fun, especially if you at first don't know the architecture very well. It's distressingly easy to reboot the system at this stage: if the 386 notices something is wrong, it shuts down and reboots - you don't even get a chance to see what's wrong. Printf() isn't very useful - a reboot also clears the screen, and anyway, you have to have access to video-mem, which might fail if your segments are incorrect etc. Don't even think about debuggers: no debugger I know of can follow a 386 into protected mode. A 386 emulator might do the job, or some heavy hardware, but that isn't usually feasible. What I used was a simple killing-loop: I put in statements like die: jmp die at strategic places. If it locked up, you were ok, if it rebooted, you knew at least it happened before the die-loop. Alternatively, you might use the sound io ports for some sound-clues, but as I had no experience with PC hardware, I didn't even use that. I'm not saying this is the only way: I didn't start off to write a kernel, I just wanted to explore the 386 task-switching primitives etc, and that's how I started off (in about April-91). After you have a minimal system up and can use the screen for output, it gets a bit easier, but that's when you have to enable interrupts. Bang, instant reboot, and back to the old way. All in all, it took about 2 months for me to get all the 386 things pretty well sorted out so that I no longer had to count on avoiding rebooting at once, and having the basic things set up (paging, timer-interrupt and a simple task-switcher to test out the segments etc). 2) Can you test the kernel functionality by running it as a process on a different OS? Wouldn't the OS(the development environment) generate exceptions in cases when the kernel (of the new OS) tries to modify 'priviledged' registers? Yes, it's generally possible for some things, but eg device drivers usually have to be tested out on the bare machine. I used minix to develop linux, so I had no access to IO registers, interrupts etc. Under DOS it would have been possible to get access to all these, but then you don't have 32-bit mode. Intel isn't that great - it would probably have been much easier on a 68040 or similar. So after getting a simple task-switcher (it switched between two processes that printed AAAA... and BBBB... respectively by using the timer-interrupt - Gods I was proud over that), I still had to continue debugging basically by using printf. The first thing written was the keyboard driver: that's the reason it's still written completely in assembler (I didn't dare move to C yet - I was still debugging at about instruction-level). After that I wrote the serial drivers, and voila, I had a simple terminal program running (well, not that simple actually). It was still the same two processes (AAA..), but now they read and wrote to the console/serial lines instead. I had to reboot to get out of it all, but it was a simple kernel. After that is was plain sailing: hairy coding still, but I had some devices, and debugging was easier. I started using C at this stage, and it certainly speeds up developement. This is also when I start to get serious about my megalomaniac ideas to make "a better minix that minix". I was hoping I'd be able to recompile gcc under linux some day... The harddisk driver was more of the same: this time the problems with bad documentation started to crop up. The PC may be the most used architecture in the world right now, but that doesn't mean the docs are any better: in fact I haven't seen /any/ book even mentioning the weird 386-387 coupling in an AT etc (Thanks Bruce). After that, a small filesystem, and voila, you have a minimal unix. Two months for basic setups, but then only slightly longer until I had a disk-driver (seriously buggy, but it happened to work on my machine) and a small filesystem. That was about when I made 0.01 available (late august-91? Something like that): it wasn't pretty, it had no floppy driver, and it couldn't do much anything. I don't think anybody ever compiled that version. But by then I was hooked, and didn't want to stop until I could chuck out minix. 3) Would new linkers and loaders have to be written before you get a basic kernel running? All versions up to about 0.11 were crosscompiled under minix386 - as were the user programs. I got bash and gcc eventually working under 0.02, and while a race-condition in the buffer-cache code prevented me from recompiling gcc with itself, I was able to tackle smaller compiles. 0.03 (October?) was able to recompile gcc under itself, and I think that's the first version that anybody else actually used. Still no floppies, but most of the basic things worked. Afetr 0.03 I decided that the next version was actually useable (it was, kind of, but boy is X under 0.96 more impressive), and I called the next version 0.10 (November?). It still had a rather serious bug in the buffer-cache handling code, but after patching that, it was pretty ok. 0.11 (December) had the first floppy driver, and was the point where I started doing linux developement under itself. Quite as well, as I trashed my minix386 partition by mistake when trying to autodial /dev/hd2. By that time others were actually using linux, and running out of memory. Especially sad was the fact that gcc wouldn't work on a 2MB machine, and although c386 was ported, it didn't do everything gcc did, and couldn't recompile the kernel. So I had to implement disk-paging: 0.12 came out in January (?) and had paging by me as well as job control by tytso (and other patches: pmacdona had started on VC's etc). It was the first release that started to have "non-essential" features, and being partly written by others. It was also the first release that actually did many things better than minix, and by now people started to really get interested. Then it was 0.95 in March, bugfixes in April, and soon 0.96. It's certainly been fun (and I trust will continue to be so) - reactions have been mostly very positive, and you do learn a lot doing this type of thing (on the other hand, your studies suffer in other respects :) Linus